Water Harvesting

Harvesting water is believed to have been developed in Ancient Iraq 4,000 to 6,000 years ago and includes practices such as diverting water across sloped areas, constructing berms to slow and direct water, and incorporating structures to collect rainwater. Mayan use of undergrounds cisterns for storing water predated the arrival of the Spanish. Runoff farming in semi-arid regions has been practiced by indigenous people of Mexico for centuries. The city of Trincheras, Sonora got its name from the trenches installed on hillsides near the city to slow water as it moved downslope during heavy rains.

Harvesting water is believed to have been developed in Ancient Iraq 4,000 to 6,000 years ago and includes practices such as diverting water across sloped areas, constructing berms to slow and direct water, and incorporating structures to collect rainwater. Mayan use of undergrounds cisterns for storing water predated the arrival of the Spanish. Runoff farming in semi-arid regions has been practiced by indigenous people of Mexico for centuries. The city of Trincheras, Sonora got its name from the trenches installed on hillsides near the city to slow water as it moved downslope during heavy rains.

More Details

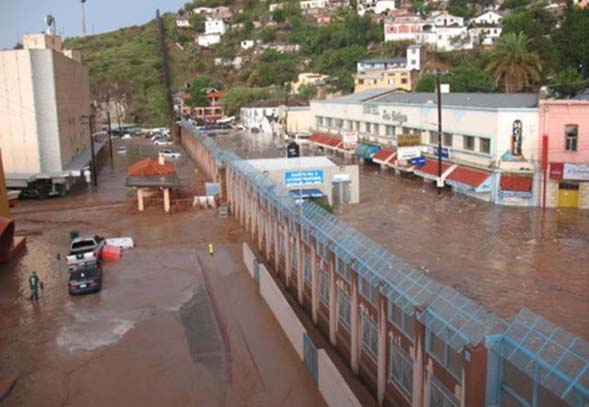

Residents and leaders of Ambos Nogales have many reasons for paying attention to water. Monthly average rainfall ranges from less than one-third of an inch in May to over 11 inches in July. The monsoon rainstorms that are a hallmark of the region exacerbate flooding and erosion on both sides of the border. In Nogales, Sonora, infrastructure has not been able to keep pace with rapid population growth, and in areas not served by the municipal water distribution system, water is brought in on trucks and pumped into tanks on the roofs of homes and businesses. Paying for water is one of the largest expenditures for many households. Many residents in the city’s outlying neighborhoods also lack access to sewer systems.

Residents and leaders of Ambos Nogales have many reasons for paying attention to water. Monthly average rainfall ranges from less than one-third of an inch in May to over 11 inches in July. The monsoon rainstorms that are a hallmark of the region exacerbate flooding and erosion on both sides of the border. In Nogales, Sonora, infrastructure has not been able to keep pace with rapid population growth, and in areas not served by the municipal water distribution system, water is brought in on trucks and pumped into tanks on the roofs of homes and businesses. Paying for water is one of the largest expenditures for many households. Many residents in the city’s outlying neighborhoods also lack access to sewer systems.

In 2001, the Ambos Nogales Revegetation Project, a collaboration of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ), Centro de Estudios Tecnológicos industrial y de servicios N. 128 (CETis 128), the Instituto Tecnológico de Nogales (ITN), and the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA) of the University of Arizona was begun to identify and protect vegetation and promote effective revegetation efforts within Ambos Nogales. After an especially dry season when neighborhoods in Nogales, Sonora were without water for extended periods, project participants realized that their success would depend on their ability to address water shortages. They began to explore passive and active water harvesting as sources of water and mechanisms for erosion control. Passive water harvesting systems redirect and slow down water to increase infiltration. Active rainwater harvesting systems channel, collect, and store rainwater for beneficial use. Both approaches also help reduce soil erosion during periods of high stormwater runoff. With assistance from the Water Resources Research Center at the University of Arizona, revegetation project partners installed a water harvesting system to support a demonstration garden at a local elementary school.

In 2002, interest in the revegetation project and its goals led to the formation of the Asociación de Reforestación en Ambos Nogales (ARAN), a coalition of schools, neighborhoods, government and business leaders, and non-governmental organizations who came together to address the specific environmental challenges facing southern Santa Cruz County, Arizona, and the municipality of Nogales, Sonora, and to draw upon lessons learned in the region to benefit other communities along the U.S.-Mexico border and elsewhere. In 2003, working with ARAN members, two students from the University of Arizona completed a pilot project installing a cistern-based water harvesting system at the Nogales home of Virginia Sinohui where the tiny driveway in front of the home had been converted into a garden.

In 2004, with funding from the U.S. EPA Border 2012 program for the “Ambos Nogales Soil Stabilization Through Vegetation project", ARAN members continued to explore active and passive water harvesting, installed structures at schools and homes to serve as demonstration sites, and conducted outreach in the form of water harvesting workshops at schools and community centers. In 2005, students from BARA and ITN installed an active rainwater harvesting system, incorporating gutters and a 10,000 liter tank, at the Casa de la Misericordia Community Center in Colonia Bella Vista in Nogales, Sonora. The system was located on a building from which water eroded loose soils as it flowed off the roof into the surrounding neighborhood, and water from the tank was pumped through the filter at the site so it could be used for drinking and cooking.

In 2004, with funding from the U.S. EPA Border 2012 program for the “Ambos Nogales Soil Stabilization Through Vegetation project", ARAN members continued to explore active and passive water harvesting, installed structures at schools and homes to serve as demonstration sites, and conducted outreach in the form of water harvesting workshops at schools and community centers. In 2005, students from BARA and ITN installed an active rainwater harvesting system, incorporating gutters and a 10,000 liter tank, at the Casa de la Misericordia Community Center in Colonia Bella Vista in Nogales, Sonora. The system was located on a building from which water eroded loose soils as it flowed off the roof into the surrounding neighborhood, and water from the tank was pumped through the filter at the site so it could be used for drinking and cooking.

Also in 2005, faculty and students from schools on both sides of the Arizona-Sonora border worked with ARAN partners to design and install water harvesting systems. For example, CONALEP hosted a workshop, led by Jesus Garcia of the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum, on the construction of passive water harvesting structures to manage rainwater runoff, prevent erosion, and provide water for vegetation and groundcover to address severe hillslope erosion at their site. CONALEP members who participated in the workshop got a head start on installing trincheras on their site, and representatives from several other groups who faced similar problems gained information and hands-on experience to take back to their groups.

Also, in 2005, faculty and students at Escuela Secundaria General 3 in Nogales, Sonora received support from ARAN partners to install tire-reinforced berms on a steep hillside between their school and a primary school below them and to install gutters and rain barrels to capture water on a large school building just above the hill and divert it to reduce erosion as well as direct water to the trees planted by students in the school’s Ecology Club.

In 2005 and 2006, faculty and students at A.J. Mitchell Elementary, Desert Shadows Middle, and Nogales High schools in Nogales, Arizona, incorporated passive water harvesting elements into their schoolyard habitats.

Drawing on the earlier experiences, in 2008, several ARAN members spearheaded a project, “Composting Toilets and Water Harvesting: Alternatives for Conserving and Protecting Water in Nogales, Sonora,” that included an active water harvesting component to demonstrate the feasibility of composting toilets, combined with rainwater harvesting, to augment municipal services. Jeremy Slack, then a student at the University of Arizona, and Jose Guadalupe Melendez Vazquez, a community leader from Colonia Flores Magón, provided key leadership for the design and installations of the water harvesting systems. Father Osvaldo Gorzegno, Pastor-Director of San Juan Bosco Parish, championed an active water harvesting demonstration project in his parish and raised funds to pay for the tank. Reina Rodelas and Apolonia Herrera Unzuenta, residents of Colonia Colinas del Sol, the neighborhood that hosted the project, graciously offered their homes as demonstration sites for the household water harvesting systems.

In 2010-2011, with support from ARAN partners, the Sonoran state water utility (CEA), and Watershed Management Group, faculty and students from several disciplines at ITN installed a tank to demonstrate the capture and utilization of stormwater onsite to reduce flooding issues, improve stormwater quality, and support vegetation to help beautify their campus.

In 2013, both passive and active water harvesting features were incorporated into the EcoCasa built on the campus of the Centro de Capacitación para el Trabajo Industrial 118 (CECATI 118) in Nogales, Sonora. The active system includes a first flush system, a 1,100 liter plastic tank purchased in Nogales, screen to keep insects and leaves out, and an overflow pipe that directs excess water onto terraces and, if needed, offsite via the access road to the site.