Composting Toilets

Composting toilet systems (also called biological toilets, dry toilets, and waterless toilets) work by providing a closed environment for human excrement and a carbon additive (usually sawdust) and then relying on aerobic bacteria and fungi to break down wastes, just as they do in a kitchen and yard waste composter. The primary objective of a composting toilet system is to contain, immobilize, or destroy organisms that cause human disease (pathogens) and reduce the risk of human infection without contaminating the immediate or distant environment and harming what lives there.

Composting toilet systems (also called biological toilets, dry toilets, and waterless toilets) work by providing a closed environment for human excrement and a carbon additive (usually sawdust) and then relying on aerobic bacteria and fungi to break down wastes, just as they do in a kitchen and yard waste composter. The primary objective of a composting toilet system is to contain, immobilize, or destroy organisms that cause human disease (pathogens) and reduce the risk of human infection without contaminating the immediate or distant environment and harming what lives there.

More Details

In some countries, such as China, composting toilets have been in use for thousands of years. In the 1860s, Reverend Henry Moule invented and patented the Earth Closet. A century later, in the 1960s, the first commercially designed composting toilet systems were sold in Scandinavia. From there the idea moved to North America, where more models were designed and marketed. Though many composting toilet projects are developed in urban areas lacking adequate sewage systems to increase public health or environmental protection, by the 21st century, modern urban systems included buildings such as the three-story Choi Building at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver which has 12 flushless toilets and urinals and saves more than 1,000 liters (264 gallons) of water per day.

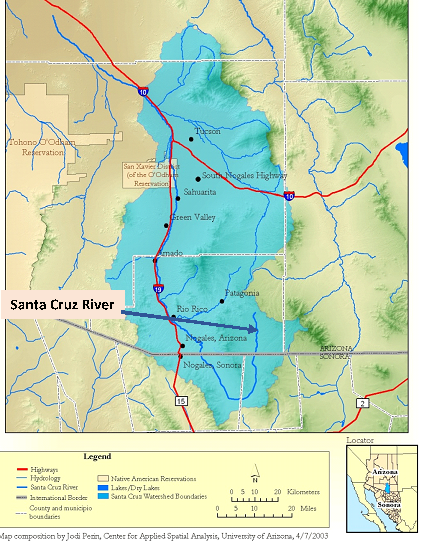

In 2002, Evan Dick, an intern at Casa de la Misericordia Community Center located in Colonia Bella Vista in Nogales, Sonora, worked with David Omick of Cascabel, Arizona and Francisco Trujillo, then-director of Borderlinks Mexico and the Community Center, to develop a pilot project to install and test composting toilets at the center and in the surrounding neighborhood. [photo] At that time, many homes in Nogales, Sonora lacked connections to potable water supplies and wastewater collection systems, with residents in the outlying, marginal colonias least likely to have either piped water or sewer connections. In 1999, researchers from Arizona State University had reported that fewer than 20 percent of residents in some parts of the municipality received these services [sadalla et al 1999 residential behavior in Nogales colonias]. Households lacking connections to the sewer system were found to use latrines or open pits for the disposal of human waste, even when those latrines were situated in dense, rocky soil with poor drainage characteristics. The ASU researchers concluded that the widespread use of latrines constituted one of the most significant environmental hazards in the region

Although by 2006 plans were underway to increase access to sewer connections through construction of a wastewater treatment plant and conveyance system in the Los Alisos basin south of Nogales (construction was completed in 2013), it was clear that many residents in Nogales would still lack water and sewer services. Without services, residents were relying on latrines, small septic pits or tanks on their property that would overflow during periods of heavy rainfall, or discharge into pipes that ultimately flowed onto streets or into washes in the neighborhood. Consequently, raw sewage continued to flow directly into the communities and the Nogales Wash, ultimately flowing through both Nogales, Sonora and Nogales, Arizona and into the Santa Cruz River. Raw sewage can contain organisms or parasites which can infect humans who drink contaminated water or eat raw or undercooked foods that have been in contact with contaminated water

Although by 2006 plans were underway to increase access to sewer connections through construction of a wastewater treatment plant and conveyance system in the Los Alisos basin south of Nogales (construction was completed in 2013), it was clear that many residents in Nogales would still lack water and sewer services. Without services, residents were relying on latrines, small septic pits or tanks on their property that would overflow during periods of heavy rainfall, or discharge into pipes that ultimately flowed onto streets or into washes in the neighborhood. Consequently, raw sewage continued to flow directly into the communities and the Nogales Wash, ultimately flowing through both Nogales, Sonora and Nogales, Arizona and into the Santa Cruz River. Raw sewage can contain organisms or parasites which can infect humans who drink contaminated water or eat raw or undercooked foods that have been in contact with contaminated water

In 2006, Francisco Trujillo expressed concerns about the ongoing problems stemming from the lack of sewer systems in eastern Nogales, and researchers from the University of Arizona Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA) worked with him during the summer and fall to design and implement an evaluation of the initial pilot project and make recommendations for a new project. [photo] During the evaluation, residents reported that the composting toilets were a positive advancement over the open pit system and demonstrated they could be operated inexpensively and safely in Nogales. Advantages of composting toilets accrue to the household, community, and the larger environment. For the household, the advantages include (1) greatly reduced water storage or supply costs; (2) production of compost; (3) reduced risk of children falling into pit holes; and (4) humus with high nutrient levels to improve soil. For the community, the advantages include (1) elimination of sewage charges, sewage pipe installations, and maintenance costs (especially when combined with graywater systems) and (2) reduction of water costs. Broader environmental benefits also include the minimization of impacts due to storage and piping, as well as the reduction of nutrient flows into washes and rivers.

During the evaluation, residents who had participated in the initial pilot project also helped the researchers identify steps that could be taken to improve other residents’ understanding and use of household composting toilets. Between 2007 and 2010, under the leadership of Cristina Rico Velázquez (president) and Martha Hernandez Lamas (secretary) of the Colinas del Sol Asociación de Vecinos (AVES), residents, community leaders, faculty, and students developed and evaluated toilet designs; established a program in Colonia Colinas del Sol to select participating households, construct toilets, and monitor their use; and offered community workshops and outreach about the safe use of composting toilets [photo of Colinas del Sol]. The project, “Composting Toilets and Water Harvesting: Alternatives for Conserving and Protecting Water in Nogales, Sonora,” was funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Border 2012 program to demonstrate the feasibility of using composting toilets to augment existing municipal wastewater services. Crucial to the project was the guidance of an advisory board that included the AVES leaders, along with Sergio Parra (Frente Cívico Municipal), Rosalva Leprón (Colegio Nacional de Educación Profesional Técnica; CONALEP), Irma Fragoso Rodriguez (Instituto Tecnológico de Nogales; ITN), and Hans Huth (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality; ADEQ), and the encouragement of the municipal government of Nogales, Sonora. By helping provide alternatives to existing latrines and pit holes, the project was designed to have the direct and immediate effects of reducing environmental contamination and improving human health.

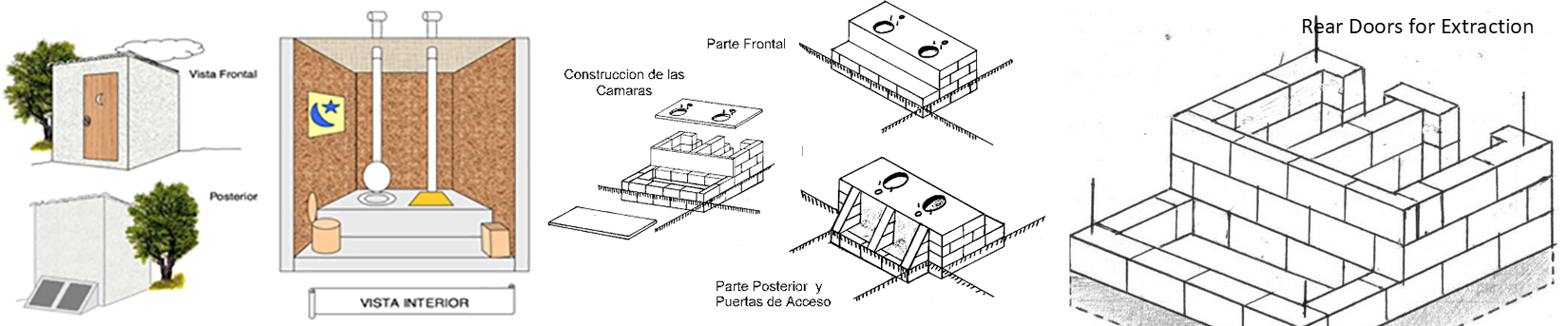

In considering whether or not to participate in the project, AVES leaders reached out to the residents of Colonia Colinas del Sol. More than 200 households indicated interest, so the advisory board established criteria for selection of project participants. Through introductory workshops, follow-up visits to the households, and a household assessment, eligible households were identified. The final toilet design modified a double chamber model developed and tested by David and Pearl Omick.

To suit local environmental and sociocultural conditions. the Nogales Double Chamber Composting Toilet does not require urine diversion and can be constructed by skilled masons using concrete blocks and cement. Users dispose of toilet paper outside the chamber and cover their deposits with sawdust. The selected participants attended a workshop on using and maintaining the composting toilet and agreed to regular monitoring of their toilet and its use. The advisory board members also decided to construct a few toilets in public locations, such as a neighborhood store and community center, to spread information about the project.

Toilet construction was taking place during the Great Recession. Rising prices of construction materials, challenges families faced meeting their financial contributions, and the logistical problems of coordinating volunteer recipient labor to construct the toilets led the project leaders to seek additional support. Friends of the Santa Cruz River, a non-profit environmental organization formed in 1991 in Santa Cruz County, Arizona to protect and enhance the flow and water quality of the river, conducted a holiday fundraising campaign through which individuals could contribute toward the purchase of a toilet in the name of someone else. This campaign successfully raised enough funds to cover the household contributions for five toilets.

In spring 2009, engineers from the City of Nogales received funding from the Mexican government to support unemployed laborers and, between 2009 and 2011, hired residents of Colinas del Sol to construct additional toilets. The project provided financial assistance for purchasing materials. In 2013, a double chamber composting toilet was constructed at the EcoCasa located on the campus of the Centro de Capacitación para el Trabajo Industrial 118 (CECATI 118).

A key aspect of the composting toilet project was the incorporation of monitoring, conducted by students and faculty from BARA, CONALEP, and ITN, to understand residents’ experiences with the toilets and patterns of use. [photo of monitoring]. Information gathered immediately after the toilets were installed was shared with project leaders so problems with construction could be addressed. Ongoing monitoring, which continued through 2009, helped identify challenges associated with using the new technology and resulted in modifications such as the provision of sawdust through the community center and of laminated posters about proper use of the toilet to hang inside the toilets. The results of the monitoring were published in Composting Toilets and Water Harvesting: Alternatives for Conserving and Protecting Water in Nogales, Sonora. To gather longitudinal data, in 2012-2013, BARA researchers returned to Colinas del Sol to follow up with residents who had received toilets to learn about their experiences. Another team of BARA researchers, working with Francisco Trujillo and with Zeida Rico Velázquez, returned to the neighborhood in 2015-2016 to again gather data on the toilets and their use [Pullen and Hilton - Composting Toilets in the Sonoran Desert- Poster presented at SEA Feb 2018].

A key aspect of the composting toilet project was the incorporation of monitoring, conducted by students and faculty from BARA, CONALEP, and ITN, to understand residents’ experiences with the toilets and patterns of use. [photo of monitoring]. Information gathered immediately after the toilets were installed was shared with project leaders so problems with construction could be addressed. Ongoing monitoring, which continued through 2009, helped identify challenges associated with using the new technology and resulted in modifications such as the provision of sawdust through the community center and of laminated posters about proper use of the toilet to hang inside the toilets. The results of the monitoring were published in Composting Toilets and Water Harvesting: Alternatives for Conserving and Protecting Water in Nogales, Sonora. To gather longitudinal data, in 2012-2013, BARA researchers returned to Colinas del Sol to follow up with residents who had received toilets to learn about their experiences. Another team of BARA researchers, working with Francisco Trujillo and with Zeida Rico Velázquez, returned to the neighborhood in 2015-2016 to again gather data on the toilets and their use [Pullen and Hilton - Composting Toilets in the Sonoran Desert- Poster presented at SEA Feb 2018].