Fibrous Concrete

Fibrous Concrete (ConFib, from the Spanish translation Concreto Fibroso) is produced with sand, waste paper, water, and small amounts of Portland cement. It has been used to build benches, walls, and even entire houses. It is non-flammable, an insulator, and an alternative to building with concrete.

Fibrous Concrete (ConFib, from the Spanish translation Concreto Fibroso) is produced with sand, waste paper, water, and small amounts of Portland cement. It has been used to build benches, walls, and even entire houses. It is non-flammable, an insulator, and an alternative to building with concrete.

More Details

The first explorations into fibrous concrete in Ambos Nogales occurred with separate efforts by Borderlinks Mexico, Inc., in 2001 and the civil engineering department at the Instituto Tecnológico de Nogales (ITN) in 2004. In 2005 to 2006, a team of researchers from the University of Arizona’s Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology (BARA) worked with various community partners, with support from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, to conduct a project entitled “Thermal Construction and Alternative Heating and Cooking Technologies.” The team assessed various technologies with the potential to reduce garbage and wood burning, thereby reducing the amount of contaminant particles that contributed to poor air quality in Ambos Nogales. One aspect of the assessment was a review of thermally efficient alternative approaches to housing construction that could be used in Nogales, Sonora, with the goals of using locally available materials and reducing the need to burn combustible materials for heating.

To evaluate local acceptance of various alternative construction technologies, faculty and students from BARA worked with representatives from Borderlinks Mexico (through the Casa de la Misericordia, a community center located in Colonia Bella Vista), Colonia Flores Magon, two Nogales, Sonora high schools, and the Asociación de Profesionales en Seguridad y Ambiente (APSA; an association of environmental health and safety managers) to organize a series of hands-on workshops and training sessions. Of the variety of possible alternative building materials that were studied and presented to civic leaders and community members in several Nogales neighborhoods, fibrous concrete was identified as the most likely to succeed as a locally-appropriate alternative. Its principal advantages for this border region were that it can be used to construct homes that look like standard cinder block homes and are secure from theft, made of readily available materials using local expertise with masonry, inexpensive, thermally efficient, absorbs sound, and is fire-, fungus-, insect-, and rodent-resistant. Fibrous concrete has an R-value of 2 to 3 per inch (compared to less than 1 for a concrete block). In addition to the initial groups, four schools, a neighborhood leader, and maquiladora managers expressed interest in further experimenting with fibrous concrete and worked with university faculty and students to hold workshops and develop projects for their sites.

The UA participants recruited Barry Fuller, founder and director of the Center for Alternative Building Studies, who provided technical assistance in the development of appropriate mixes for walls, roofs, and mortar; in the construction of an efficient, low cost mixer for use in the construction process; and in the construction of two structures. During 2005-2006, one high school in Nogales, Sonora, Centro de Estudios Tecnológicos industrial y de servicios N. 128 (CETis 128), held workshops, and students from the school’s ecology club began experimenting with the material. The second school, Colegio Nacional de Educación Profesional Técnica (CONALEP), also held workshops and utilized its metal shop to construct a mixer for use throughout Nogales. Two schools in Nogales, Arizona, A.J. Mitchell Elementary and Desert Shadows Middle, helped test the material by constructing schoolyard benches from the material. After the first workshop, Guadalupe Melendez, a neighborhood leader from Colonia Flores Magón began to produce blocks by hand. He built a wall near his house to test the material and demonstrate its potential to his neighbors. Concerned that the common English name for the material, papercrete, would not reflect the strength and durability of the material, the binational group settled on the name fibrous concrete (concreto fibroso, which became popularlized as ConFib).

During 2006-2007, structures made of fibrous concrete were begun in two colonias in Nogales, Sonora, and the material and process were further modified to be better adapted to local conditions. After completing the wall and observing how well it held up in Nogales’ climate, but still facing much skepticism, Mr. Melendez began to construct a small apartment of fibrous concrete near his house. One of his neighbors watched, learned how to make the blocks, and began constructing a room on his own property. In April 2007, APSA held a block construction contest for its members, resulting in the production of more than 800 blocks. In the fall of 2007, Mr. Melendez organized Grupo ConFib Flores Magón, a grassroots organization dedicated to promoting and producing fibrous concrete blocks. Also that fall, a group of managers and engineers from Alcatel-Lucent, a Nogales maquiladora, held another block-making event and committed to the construction of a model house for one of its employees. The company solicited and received assistance from a local construction company and manufacturer. Despite delays caused by acquiring and transporting materials, working around other jobs and responsibilities, and halting construction through the summer rainy monsoon season, both structures were completed by the late summer of 2008. During the construction of these two structures, investigations of the material’s acceptability to residents, government regulators, and architects and engineers; and of the material’s performance under differing weather conditions and with various ratios of paper, sand, and cement continued.

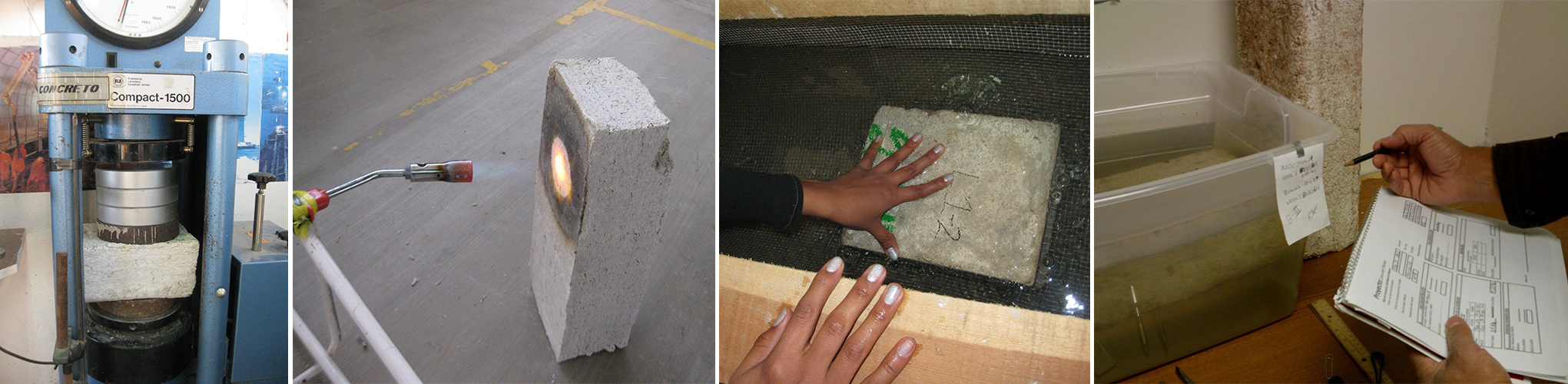

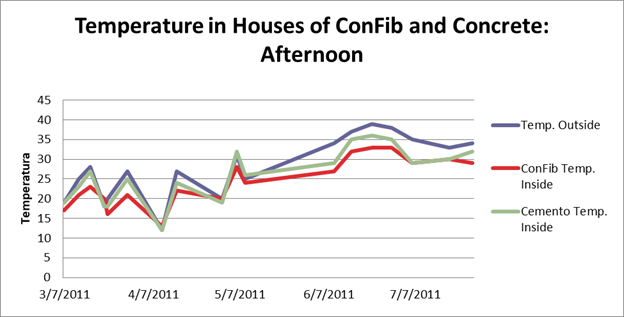

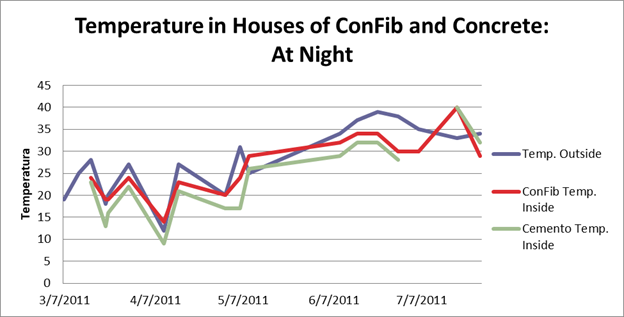

During 2009 and 2010, individuals and institutions in Nogales and Tucson continued to experiment with fibrous concrete and develop a process for producing the material that was more economical, efficient, and suitable for Nogales. Between 2011 and 2012, with funding from the U.S. EPA Border 2012 program, collaborators from CECATI 118, ConFib Flores Magon, BARA, and ITN developed a demonstration facility to produce blocks, wall and roof panels, and mortar; and evaluated various fibrous concrete mixtures and processes. Data were collected on Compression Strength, Volumetric Weight, Specific Weight, Adsorption and Absorption of Humidity, and Fire Resistance. The group constructed the EcoCasa, a demonstration structure in the manner typical of self-help and small-scale housing construction as it was carried out in Nogales in order to have the basis for estimating the costs of a typical, one-room structure; track all inputs and costs; and provide recommendations for a sustainable program that would best utilize materials in the Nogales waste stream. The collaborators also monitored temperature differentials in an existing house made of fibrous concrete and a standard concrete block house. The results of these investigations were published in From Waste to Resource: Fibrous Concrete as an Alternative to Landfilling and Burning Paper in Nogales, Sonora.

During 2009 and 2010, individuals and institutions in Nogales and Tucson continued to experiment with fibrous concrete and develop a process for producing the material that was more economical, efficient, and suitable for Nogales. Between 2011 and 2012, with funding from the U.S. EPA Border 2012 program, collaborators from CECATI 118, ConFib Flores Magon, BARA, and ITN developed a demonstration facility to produce blocks, wall and roof panels, and mortar; and evaluated various fibrous concrete mixtures and processes. Data were collected on Compression Strength, Volumetric Weight, Specific Weight, Adsorption and Absorption of Humidity, and Fire Resistance. The group constructed the EcoCasa, a demonstration structure in the manner typical of self-help and small-scale housing construction as it was carried out in Nogales in order to have the basis for estimating the costs of a typical, one-room structure; track all inputs and costs; and provide recommendations for a sustainable program that would best utilize materials in the Nogales waste stream. The collaborators also monitored temperature differentials in an existing house made of fibrous concrete and a standard concrete block house. The results of these investigations were published in From Waste to Resource: Fibrous Concrete as an Alternative to Landfilling and Burning Paper in Nogales, Sonora.

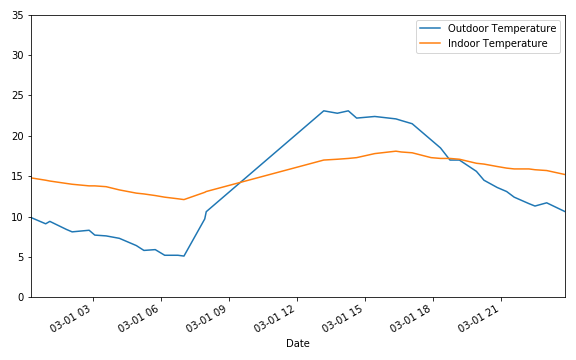

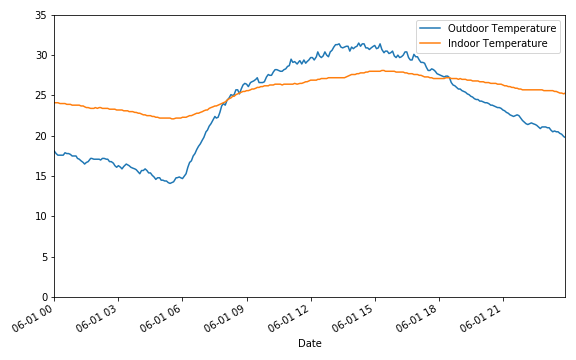

In 2019, a weather station was installed at the EcoCasa. The station records data on local environmental conditions at the EcoCasa, including exterior temperature and dewpoint, interior temperature and humidity, and a calculated heat index (thermal comfort, wind chill, etc.). It also records data on precipitation, barometric pressure, air quality (PM 2.5), solar radiation, wind speed and direction, and a UV index. The interior and exterior temperature and heat index data are especially relevant to the EcoCasa and the ConFib, as they demonstrate the buffering effect of these blocks in limiting exposure to temperature extremes.

The interior temperature is more stable and less variable, with nighttime interior temperatures being higher than the exterior temperature, but more importantly, daytime interior temperatures are lower than the exterior temperature. This means summertime heat is mitigated by the ConFib,and provides some relief from exposure to high temperatures (note: the EcoCasa has no climate control cooling system). This same pattern is present during cooler months, but instead of buffering the heat of the daytime temperatures, the important fact is that interior temperatures are warmer than exterior temperatures overnight, reducing exposure to colder temperatures and reducing the need to use heating systems. The following graphs illustrate daily and seasonal patterns that highlight how ConFib buffers against heat in the summertime and cold in the winter, and the data portal (below) links to the interior and exterior temperature monitoring system.